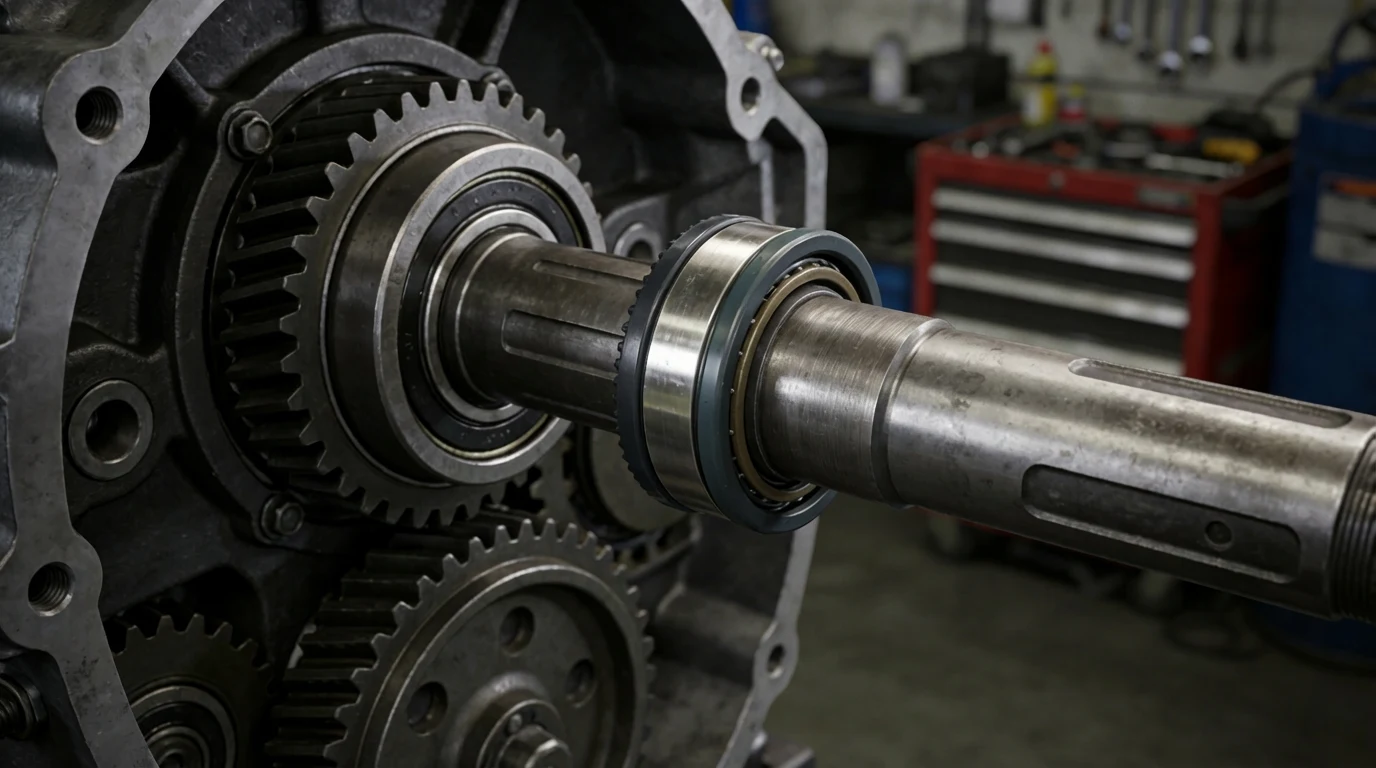

Introduction: Sealing a World in Motion

In the domain of sealing technology, the challenges presented by static and reciprocating applications, while complex, are fundamentally different from those encountered when sealing a rotating shaft. A static seal must simply contain pressure between non-moving components, while a reciprocating seal must manage a back-and-forth motion. A rotary sealing ring, however, must contend with a surface that is in a state of perpetual, high-speed, unidirectional motion. This constant movement introduces a new and formidable set of physical challenges: significant frictional heat generation, dynamic runout, shaft vibrations, and the complex fluid dynamics required to maintain a seal without self-destructing. The reliability of virtually every piece of rotating equipment—from an automotive engine crankshaft and a gearbox to an industrial pump and an electric motor—is directly dependent on the performance of these specialized seals.

Commonly known as Oil Seals or radial shaft seals, these components are precision-engineered devices designed to perform a dual function: retain lubricants within the system and exclude external contaminants. The success or failure of a rotary sealing ring is not just a matter of preventing a leak; it is a critical factor in the longevity of the bearings and gears that the seal is designed to protect. An inadequate seal can lead to lubricant starvation, bearing failure, and ultimately, catastrophic equipment seizure. This guide provides a comprehensive exploration of the world of rotary sealing. We will delve into the fundamental physics that govern a rotary sealing ring’s function, deconstruct the anatomy of the common radial lip seal, analyze the critical role of material science in handling friction and heat, and examine the best practices in shaft preparation and installation that are paramount for achieving a long and reliable service life.

The Unique Physics of Rotary Sealing: The Hydrodynamic Film

The secret to a successful dynamic rotary sealing ring lies in a concept that may seem counterintuitive: a controlled, microscopic leak. A rotary sealing ring does not function by creating a perfectly dry, zero-contact barrier against the shaft. If it did, the friction from the high-speed rubbing would generate immense heat, causing the seal lip to burn up and fail within minutes. Instead, the seal is designed to operate on a principle known as hydrodynamic lubrication. As the shaft rotates, it pulls a minute amount of the lubricant (typically oil or grease) underneath the seal lip. The shear forces within this fluid layer create a localized pressure that lifts the sealing lip away from the shaft by a microscopic distance, typically just 1 to 3 micrometers.

This incredibly thin layer of fluid, the hydrodynamic film, is the key to the seal’s survival and performance. It serves two vital purposes:

- Lubrication: It creates a barrier that separates the two moving surfaces (the seal lip and the shaft), dramatically reducing the coefficient of friction and preventing abrasive wear.

- Heat Dissipation: The lubricant in the film is constantly being exchanged with the bulk oil in the system, acting as a coolant that carries away the frictional heat generated at the sealing interface.

The seal’s design is engineered to maintain this delicate balance. The geometry of the sealing lip and the contact pressure it exerts are precisely controlled to allow for the formation of this film without permitting a visible leak. Some advanced seal designs even incorporate microscopic hydrodynamic aids—tiny ribs or asperities molded into the lip—that act as miniature pumps, actively channeling any excess fluid that passes the primary sealing edge back into the system. Understanding this principle is fundamental; the goal of rotary sealing is not to create a perfect dam, but to manage a highly controlled, life-sustaining micro-leak.

Anatomy of the Workhorse: Deconstructing the Radial Lip Seal

The most common type of rotary sealing ring is the radial lip seal, often referred to simply as an oil seal. While appearing simple, it is a precision-engineered assembly of several key components, each with a specific role. A typical design, such as the widely used TC Oil Seal, provides a perfect model for understanding this construction.

1. The Metal Case (Outer Ring)

The metal case provides the structural backbone of the seal. Its primary function is to create a secure, static press-fit seal in the housing bore. This ensures the seal remains fixed in its position and prevents leakage around the outside diameter. The case is typically made of carbon steel and may be fully or partially encapsulated in rubber to improve its sealing capability against minor imperfections in the housing bore.

2. The Sealing Lip (Primary Lip)

This is the most critical functional part of the seal. It is a flexible, elastomeric lip that is molded with a precise interference fit relative to the shaft diameter. This interference creates the initial radial load, or contact pressure, on the shaft. The tip of the sealing lip is precision-trimmed or molded to a sharp edge to create a defined contact band on the shaft, which is essential for managing the hydrodynamic film. The geometry of the lip—its angle, thickness, and flexibility—is carefully designed to respond to shaft dynamics while maintaining a stable sealing force.

3. The Garter Spring

The garter spring is a coiled steel spring with its ends joined to form a circle, which sits in a groove molded into the back of the primary sealing lip. Its purpose is to augment the initial radial load provided by the elastomeric interference. More importantly, it provides a consistent and continuous radial force throughout the seal’s life, compensating for any material relaxation (compression set), thermal expansion, or wear. This ensures that the seal maintains its effectiveness even as it ages and is subjected to varying temperatures.

4. The Dust Lip (Secondary Lip)

Many oil seals, including the “TC” (which stands for Triple Contact, or more commonly, a rubber-covered case with a spring and a dust lip), feature a secondary, non-spring-loaded lip. This dust lip points outwards and makes light contact with the shaft. Its sole purpose is to act as an excluder, preventing dust, dirt, and other external contaminants from reaching the primary sealing lip and the bearing area. It is a crucial feature for seals used in dirty or dusty environments.

Material Science: The Key to Performance Under Duress

The selection of the elastomeric material for the sealing lip is one of the most critical decisions in specifying a rotary sealing ring. The material must be able to withstand the operating temperature, be chemically compatible with the lubricant, and possess excellent wear resistance to endure millions of high-speed rotations. The choice of Sealing Materials dictates the seal’s performance window.

Common Rotary Sealing Ring Materials:

- Nitrile (NBR): This is the most widely used material for general-purpose oil seals. It offers an excellent balance of properties, including very good resistance to petroleum-based oils and fuels, high abrasion resistance, and a competitive cost. Its primary limitation is its temperature range, typically up to 100°C (212°F).

- Polyacrylate (ACM): ACM offers better heat resistance than NBR, typically up to 150°C (302°F). It is often used in automotive applications like automatic transmissions where temperatures exceed the limits of Nitrile.

- Fluorocarbon (FKM/Viton™): FKM is a high-performance choice known for its exceptional resistance to high temperatures (up to 200°C / 392°F), a broad range of chemicals, and modern synthetic lubricants. It is the go-to material for demanding industrial, automotive, and chemical applications where NBR would fail.

High-Performance Solutions: The Rise of PTFE Seals

For applications that exceed the capabilities of traditional elastomers, particularly those involving very high shaft speeds, aggressive media, or dry-running conditions, Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) has emerged as the material of choice. A PTFE Oil Seal, often housed in a stainless steel case for corrosion resistance, offers a unique set of advantages:

- Extremely Low Friction: PTFE has one of the lowest coefficients of friction of any solid, which means it generates significantly less heat, allowing for much higher shaft surface speeds (often double or triple that of elastomeric seals).

- Wide Temperature Range: PTFE can handle a vast temperature range, from cryogenic conditions up to 260°C (500°F).

- Superior Chemical Resistance: It is virtually inert to all industrial chemicals and solvents.

- Dry-Running Capability: Its low-friction nature allows it to survive for periods of poor lubrication or even dry running that would destroy an elastomeric seal.

PTFE lip seals are not elastomeric, so they do not use a garter spring. Instead, their lip is designed to be energized by system pressure. They are a premium solution for the most challenging rotary sealing applications, such as high-speed gearboxes, compressors, and specific Gear Pump Seals.

Critical Success Factors: Shaft and Housing Considerations

A rotary sealing ring is only one half of a sealing system. The shaft and housing bore are the other half, and their condition is equally critical to achieving a reliable, long-lasting seal. Even the highest-quality seal will fail prematurely if installed on an improperly prepared shaft.

1. Shaft Surface Finish

The finish of the shaft surface that contacts the seal lip is paramount. If it is too rough, it will act like a file, abrading the seal lip and causing a rapid leak. If it is too smooth (a mirror finish), it may not be able to retain the necessary hydrodynamic oil film, leading to lubrication starvation and high friction. The industry standard is typically a plunge-ground finish with a roughness of 0.2 to 0.8 µm Ra (8 to 32 µin Ra). Importantly, there should be no machining lead lines (spiral grooves), as these can act as a pump, transferring oil out of the system.

2. Shaft Hardness

The shaft must be hard enough to resist grooving and wear. A soft shaft will quickly develop a groove from the seal lip’s contact, especially if abrasive contaminants are present. A minimum hardness of 30 HRC is recommended for general applications, while for heavy-duty or abrasive environments, a hardness of 55-60 HRC is preferred.

3. Shaft and Bore Tolerances

The shaft diameter and housing bore must be machined to the correct tolerances to ensure the proper interference fit for both the seal lip on the shaft and the seal case in the housing. Eccentricity, or the misalignment between the center of the shaft’s rotation and the center of the housing bore (dynamic runout), must also be minimized, as it forces the seal lip to flex continuously, which can lead to fatigue and leakage.

4. Installation Best Practices

Improper installation is one of the leading causes of immediate seal failure. Key practices include:

- Cleanliness: The seal, shaft, and bore must be perfectly clean.

- Lubrication: Generously lubricate the seal lip and the shaft with the system fluid before installation.

- Proper Tooling: Use a dedicated installation tool with a flat face to press the seal into the bore squarely. Never use a hammer and screwdriver, as this will damage the case and cause the seal to be installed crooked.

- Protecting the Lip: The seal lip is delicate. When sliding the seal over a shaft that has keyways, splines, or sharp edges, a protective installation sleeve must be used to prevent the lip from being cut or nicked.

Conclusion: The Precision Engineering of Rotary Reliability

Sealing a rotating shaft is a formidable engineering challenge that demands a sophisticated and precisely manufactured solution. The modern radial lip seal, in its many forms, is a testament to decades of research in fluid dynamics, material science, and tribology. It is a component that operates on a knife’s edge, balancing the need to contain a fluid with the necessity of allowing a microscopic film to pass for its own survival. From the general-purpose reliability of a standard TC oil seal to the high-performance capabilities of a specialized PTFE design, the selection of the correct rotary sealing ring is fundamental to the efficiency and longevity of rotating machinery.

Achieving success, however, extends beyond the seal itself. It requires a holistic system approach that gives equal importance to the preparation of the shaft, the precision of the housing, and the meticulous care taken during installation. By understanding the intricate physics at play and adhering to established engineering best practices, we can ensure these critical components perform their duty reliably, keeping our mechanical world in constant, well-lubricated motion.