What Are Seals and Why Are They a Cornerstone of Modern Machinery?

The Fundamental Principles of Sealing Technology

At its core, the function of a seal is to create a barrier between two distinct environments. The effectiveness of this barrier is governed by a set of fundamental principles rooted in physics and material science. The primary goal is to close the gap between mating surfaces to a degree that prevents the passage of a fluid or gas. This is achieved by generating a contact stress at the sealing interface that is greater than the pressure of the fluid being contained. The seal must be sufficiently deformed by an initial “squeeze” or interference fit upon installation to fill any microscopic imperfections, such as scratches or tool marks, on the mating hardware surfaces, which allows elastomeric materials—especially elastomeric seals such as O-rings—to fill microscopic surface imperfections. This initial compression creates the primary sealing line.

Once the system is pressurized, the fluid pressure itself often acts on the seal, energizing it and forcing it more firmly against the mating surfaces. This self-energizing principle is a key design feature in many seal types, including the ubiquitous O-Rings. The seal’s material properties, particularly its elasticity and compression set resistance, are critical. Elasticity allows the seal to conform to the hardware surfaces and return to its original shape after the deforming load is removed. Compression set resistance is the material’s ability to resist permanent deformation after being held in a compressed state, ensuring it can maintain sealing force over long periods. Furthermore, factors like surface tension of the sealed fluid, the surface finish of the hardware, and the operating temperature all play a crucial role. A rougher surface requires a softer, more compliant seal material to fill the asperities, while higher temperatures can cause materials to soften or degrade, compromising the sealing force. Understanding these interplay of forces, material responses, and system conditions is fundamental to selecting and designing a reliable sealing solution.

A Comprehensive Classification of Industrial Seals

The vast array of applications for industrial seals has led to the development of a diverse and specialized range of seal types, each engineered to meet specific operational demands. These can be broadly classified based on their design, function, and the type of motion they accommodate. A primary distinction is between static seals, which operate between surfaces with no relative motion, and dynamic seals, which function between surfaces that move relative to each other.

Elastomeric Seals

This is perhaps the most common category, valued for its versatility and cost-effectiveness.

- O-Rings: These are circular rings with a circular cross-section, typically made of elastomeric materials. They are used in both static and dynamic applications and are one of the most common seals used in machine design. For applications requiring extreme chemical resistance, Encapsulated O-Rings, which feature an elastomer core within a seamless polymer jacket, offer a robust solution.

- Gaskets: These are mechanical seals which fill the space between two or more mating surfaces, generally to prevent leakage from or into the joined objects while under compression. PTFE Gaskets are highly sought after for their chemical inertness and wide temperature range.

Hydraulic and Pneumatic Seals

Designed specifically for fluid power systems, these seals are critical for converting fluid pressure into linear or rotary motion.

- Piston Seals: These are located in the cylinder head and seal against the cylinder bore, preventing fluid from bypassing the piston. This is essential for maintaining pressure and generating force. Examples include the GSF Piston Seal (Glyd Ring), the SPG Piston Seal, and the high-performance SPGW Piston Seal.

- Rod Seals: These are located in the cylinder head and seal against the reciprocating piston rod, preventing leakage of hydraulic fluid from the cylinder to the outside.

- Wiper Seals: Also known as scrapers, their function is to prevent external contaminants like dirt, dust, and moisture from entering the cylinder as the rod retracts.

- Cushion Seals: These specialized seals, such as COP Cushion Seals, are used at the end of a cylinder’s stroke to decelerate the piston, preventing impact damage.

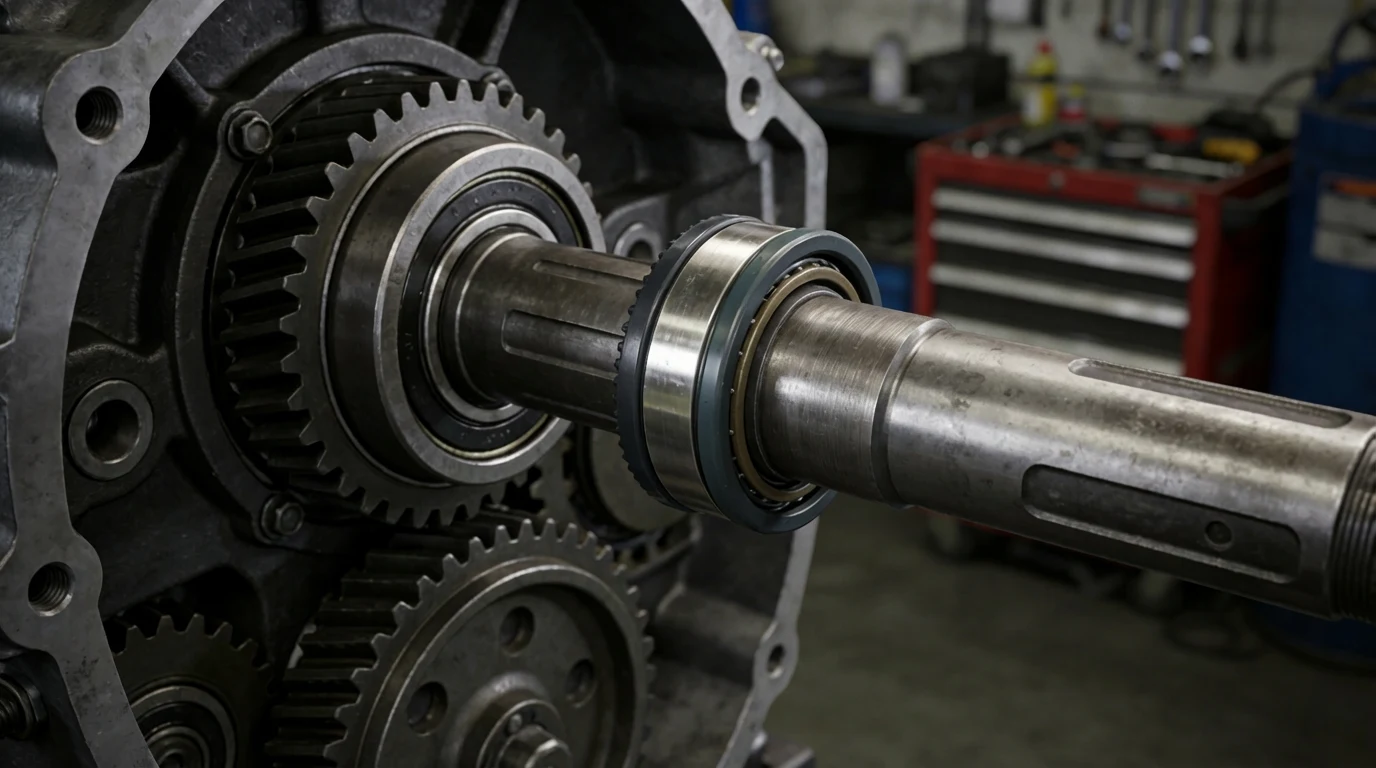

Rotary Seals

These are used in applications involving a rotating shaft, where the challenge is to contain fluid and exclude contaminants while accommodating constant motion.

- Oil Seals (Rotary Shaft Seals): These typically consist of a metal case, an elastomeric sealing lip, and a garter spring. The spring helps maintain a constant radial force of the lip against the shaft. The TC Oil Seal is a common design, while PTFE Oil Seals are used for more demanding applications involving high speeds or aggressive media.

- Pump Seals: Mechanical seals used in pumps are more complex, often consisting of a stationary and a rotating face that are lapped to a high degree of flatness to create a sealing interface. Specific designs like Gear Pump Seals are engineered for the specific challenges of that application.

High-Performance and Specialty Seals

For applications with extreme conditions, specialized seals are required.

- Spring Energized Seals: These seals use a spring, such as a Helical Spring or a Meander V-Spring, to provide the initial sealing force. This makes them ideal for low-pressure, cryogenic, or high-temperature applications where elastomers would fail. The seal jacket is typically made from high-performance polymers like PTFE.

- Metal Seals: For the most extreme conditions of temperature, pressure, and radiation, metal seals are used. Hollow Metal O-Rings can provide a robust seal in applications like nuclear reactors, gas turbines, and vacuum systems.

- Compressor Parts: Components like PEEK Valve Plates serve a sealing function within air compressors, requiring materials that can withstand high temperatures and rapid cycling.

Dynamic vs. Static Seals: Understanding the Critical Distinction

The distinction between dynamic and static sealing applications is one of the most fundamental concepts in seal selection and design. A static seal is used between two mating surfaces that do not move relative to one another. Examples include the seal on a flange cover, a pipe fitting, or the face seal on a hydraulic port. The primary challenges for a static seal are to withstand the system pressure and temperature, resist the chemical environment, and maintain its sealing force over a long period without significant degradation or compression set. The design considerations focus on ensuring sufficient initial squeeze to fill surface imperfections and selecting a material that will remain stable under the specific operating conditions. Gaskets and O-rings in face-seal configurations are classic examples of static seals.

Dynamic seals, in contrast, are required to create a barrier between two components that are in relative motion. This motion introduces a host of complex challenges, including friction, wear, heat generation, and the need to maintain a lubricating film. Dynamic applications can be further categorized into reciprocating (back-and-forth linear motion, as with a hydraulic cylinder rod), rotating (motion around an axis, as with a driveshaft), and oscillating (pivoting back and forth over a limited angle). For a dynamic seal to function correctly, it must manage the thin film of fluid (lubricant) that passes between the seal and the moving surface. Too thick a film results in unacceptable leakage; too thin a film leads to excessive friction, heat generation, and rapid wear of both the seal and the hardware. This delicate balance is the essence of dynamic seal design. Components like Oil Seals and Piston Seals are quintessential dynamic seals, and their design, material, and the surface finish of the moving component are all critically interdependent for achieving a long and reliable service life.

For deeper reference on dynamic seal behavior, clearance design, and friction management, engineers may consult the SKF Seal Technical Guide, which provides extensive data on rotary and reciprocating sealing systems: https://www.skf.com/group/products/seals

Material Science in Sealing: Choosing the Right Compound for the Job

The performance of any seal is inextricably linked to the properties of the material from which it is made. The selection of the optimal sealing material is a complex process that involves balancing multiple, often competing, requirements, including chemical compatibility, temperature range, pressure rating, wear resistance, and cost. An inappropriate material choice is one of the leading causes of premature seal failure. The universe of sealing materials is vast, but they can be grouped into several main families.

Elastomers (Rubbers)

These are the most common sealing materials due to their flexibility and resilience.

- Nitrile (NBR): A workhorse material, offering excellent resistance to petroleum-based oils and fuels, and good physical properties. It is widely used in standard hydraulic and pneumatic applications.

- Fluorocarbon (FKM/Viton™): Known for its excellent resistance to high temperatures, petroleum oils, and a wide range of chemicals. It is a premium choice for demanding applications in the automotive, aerospace, and chemical processing industries.

- Silicone (VMQ): Offers an outstanding temperature range, both high and low, and is resistant to weathering and ozone. However, it has poor tear strength and abrasion resistance, making it better suited for static applications.

- Ethylene Propylene (EPDM): Provides excellent resistance to water, steam, and polar fluids like brake fluid, but is not suitable for use with petroleum oils.

Thermoplastics and Fluoropolymers

These materials offer enhanced properties for more challenging applications.

- Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE): Famous for its near-universal chemical resistance, extremely low coefficient of friction, and wide temperature range. Its main drawback is a tendency to creep or cold-flow under load. It is often filled with other materials (like glass, carbon, or bronze) to improve its mechanical properties. It’s the material of choice for components like Gaskets, PTFE Cord, and the jackets of spring-energized seals.

- Polyether Ether Ketone (PEEK): A high-performance semi-crystalline thermoplastic with exceptional mechanical strength, stiffness, and thermal stability. It is used in high-stress applications like compressor valve plates and backup rings.

- Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET): A strong, stiff engineering plastic with good chemical resistance and low moisture absorption. It can be used for components like precision PET Balls in check valves.

Metals

For the most extreme environments where polymers cannot survive.

- Stainless Steel: Used for the casings of oil seals and for springs in spring-energized seals (SS301) due to its corrosion resistance and strength.

- Inconel® and other Nickel Alloys: Selected for Metal Seals in ultra-high temperature and corrosive environments, such as those found in aerospace and nuclear applications.

The selection process requires a detailed analysis of the application’s STAMPS criteria: Size, Temperature, Application, Media, Pressure, and Speed. By carefully considering each of these factors, an engineer can navigate the vast landscape of available Sealing Materials to identify the compound that will deliver the most reliable and long-lasting performance.

Common Causes of Seal Failure and Proactive Prevention Strategies

Despite careful design and selection, seal failure is a common maintenance issue that can lead to costly downtime and equipment damage. Understanding the root causes of these failures is the first step toward effective prevention. A post-mortem analysis of a failed seal often reveals tell-tale signs that point to a specific failure mode. Proactive prevention involves not only selecting the right seal but also ensuring proper installation and system maintenance.

Common Failure Modes:

Seal failure is a major maintenance concern, and understanding its causes is essential for seal failure prevention.

- Compression Set: The seal fails to return to its original shape after being compressed, resulting in a flat-sided appearance. This reduces the sealing force and leads to leakage. It can be caused by excessive temperature, improper material selection, or an oversized seal for the groove.

- Extrusion and Nibbling: Under high pressure, the seal is forced into the clearance gap between the mating components, leading to a “nibbled” or chewed appearance. This is prevented by reducing clearances, increasing material hardness, or using anti-extrusion backup rings.

- Spiral Failure: This occurs in long-stroke reciprocating applications, where the seal gets twisted in its groove, resulting in deep, spiral-shaped cuts on its surface. It can be caused by inconsistent lubrication, surface finish irregularities, or improper installation.

- Thermal Degradation: Exposure to temperatures beyond the material’s limit can cause it to become hard and brittle, leading to cracking and loss of elasticity. This is indicated by a darkened, cracked, or even crumbly appearance.

- Chemical Attack: The seal material swells, softens, or dissolves due to incompatibility with the system fluid. Prevention requires a thorough review of chemical compatibility charts before material selection.

- Abrasion: The seal surface appears worn or has a circumferential scratch. This is caused by contact with a rough mating surface or the presence of abrasive particles in the system fluid. Proper filtration and ensuring correct hardware surface finishes are key preventative measures.

- Improper Installation: Nicks, cuts, or scratches on the seal that occur during installation are a very common cause of immediate leakage. This can be avoided by using proper installation tools, lubricating the seal and hardware, and ensuring lead-in chamfers are present and free of burrs.

Prevention Strategies:

A robust prevention strategy is multi-faceted. It begins with a comprehensive analysis of the application to ensure the correct seal profile and material are selected. This includes considering all operating parameters, including potential temperature spikes or pressure surges. Hardware design is equally important; groove dimensions must be correct, surface finishes must meet specifications, and clearance gaps must be minimized. Cleanliness during assembly is paramount to prevent contaminant-induced abrasion. Finally, proper installation procedures, including the use of lubrication and appropriately designed tools, can prevent the majority of early-life failures. Regular system maintenance, such as fluid analysis and filter changes, will further contribute to extending the life of all sealing components, from simple O-Rings to complex Pump Seals.

The Future of Sealing Technology: Innovations on the Horizon

The field of sealing technology is in a constant state of evolution, driven by the relentless demands of industry for greater efficiency, higher performance, and improved environmental compliance. Several key trends and innovations are shaping the future of how we contain fluids and exclude contaminants. One of the most significant areas of development is in material science. New polymer formulations are being created that offer wider temperature ranges, enhanced chemical resistance, and superior wear properties. Self-healing elastomers are moving from the laboratory to practical application, promising industrial seals that can repair minor damage in-situ, dramatically extending service life and reducing maintenance intervals. The integration of nanoparticles and other advanced fillers is creating composite materials with unprecedented combinations of strength, lubricity, and resilience.

Another major frontier is the development of “smart seals.” These are seals embedded with micro-sensors that can monitor their own condition in real-time. They can provide data on temperature, pressure, and wear, feeding this information back to a central control system. This enables predictive maintenance, allowing a seal to be replaced just before it fails, rather than on a fixed schedule or after a catastrophic leak has already occurred. This technology has the potential to revolutionize maintenance practices, increasing safety and reducing operational costs. Furthermore, advancements in manufacturing, such as additive manufacturing (3D printing), are enabling the rapid prototyping and production of complex seal geometries that are optimized for specific applications, a feat not possible with traditional molding techniques. As machinery continues to push the boundaries of speed, pressure, and temperature, and with increasing focus on reducing fugitive emissions and improving energy efficiency, the role of innovative sealing technology will only become more critical. The future will see industrial seals that are not just passive components, but active, intelligent parts of an integrated mechanical system.

Conclusion: The Unsung Heroes of Mechanical Integrity

Industrial seals are the quintessential unsung heroes of the mechanical world. They operate silently and largely unseen, yet their proper function is absolutely critical to the safety, reliability, and efficiency of virtually every piece of machinery in our modern world. From the simple O-ring that prevents a minor leak to the highly engineered spring-energized seal operating in a cryogenic pump, these components represent a sophisticated blend of material science, physics, and mechanical design. The journey through their fundamental principles, diverse classifications, and the critical differences between static and dynamic applications reveals a field of remarkable depth and complexity.

A successful sealing solution is built on a foundation of knowledge: understanding the demands of the application, selecting the appropriate material, recognizing the signs of potential failure, and adhering to best practices in design and installation. As industries continue to advance, demanding higher performance under more extreme conditions, the technology of sealing will continue to evolve in lockstep. By appreciating the critical role of these components and investing in high-quality sealing solutions, we ensure the integrity and longevity of the machines that power our world. They may be small, but their impact is immeasurable, proving that in engineering, even the most minor component can be of major importance.