To the untrained eye, hydraulic seals appear to be simple piece of rubber. Ideally, it is just a barrier. However, in reality, a working hydraulic seal is a complex mechanical device by sealing mechanics. It interacts with fluids, metal surfaces, and extreme forces according to the laws of physics. Understanding these forces is the key to effective leakage control. For engineers seeking global benchmarks in hydraulic seals and leakage control, it’s important to reference industry standards. Authoritative specifications and testing protocols for sealing components and related materials are available from the International Organization for Standardization — explore comprehensive guidelines at ISO Standards.

At QZSEALS, we approach sealing as a science—specifically, the science of Tribology (friction, wear, and lubrication) and Fluid Dynamics. Our mission is to engineer solutions that harness these physical laws to ensure reliability in hydraulic seals and other industrial components.

This technical guide goes beyond the catalog. We will explore the fundamental sealing mechanics. We will explain how a seal creates a barrier, how pressure energization helps a seal perform, and how we manage the delicate balance between sealing force, static friction, and wear.

Principle 1: Initial Squeeze (Pre-Load)

A seal must work even when the system is off. This is called low-pressure sealing capability. To achieve this, the seal is designed to be slightly larger than the groove it sits in.

The Interference Fit

When an O-Ring Rubber Seal is installed, it is compressed. This “squeeze” creates contact stress between the seal and the mating metal surfaces.

- Static Sealing: In a flange, this squeeze blocks the potential leak path. The resilience of the rubber pushes back against the metal, creating a tight joint.

- Dynamic Sealing: For a UNS Piston Rod Seal, the lips are flared slightly wider than the rod diameter. Upon insertion, they are compressed, ensuring contact even at zero pressure.

Engineering Challenge: If the squeeze is too low, the seal leaks at start-up. If it is too high, friction becomes excessive, causing wear. QZSEALS designs profiles with precise interference to balance this.

Principle 2: Pressure Energization

Once the system turns on, physics takes over. Hydraulic seals are “pressure-actuated.” This means they use the fluid’s own pressure to increase the sealing force.

The Pascal’s Law Effect

Pascal’s Law states that pressure applied to a confined fluid is transmitted equally in all directions.

When oil enters the groove of a U-Cup style seal like the IDI Rod Seal, it pushes against the back of the seal lips.

- System Pressure = Sealing Force: As system pressure rises, it forces the seal lips tighter against the rod and the groove wall.

- The Result: The higher the pressure, the harder the seal bites. This is why a seal might leak at low pressure but seal perfectly at high pressure.

Spring Energization

What if there is no fluid pressure? In vacuum or low-pressure gas applications, we cannot rely on the fluid. We must provide mechanical energy.

This is the function of the Spring Energized Seal. A metal spring (Helical or Meander) physically pushes the lips out, mimicking the effect of fluid pressure.

Principle 3: Oil Film Lubrication

A dynamic seal should never run completely dry. If a rubber seal rubs against dry steel, it generates massive heat and fails instantly. A successful seal actually rides on a microscopic film of oil.

The Oil Film Paradox

The engineering goal is contradictory: let enough oil pass to lubricate the seal, but not enough to constitute a leak.

- Outstroke: As the rod extends, the seal allows a thin film of oil to pass under the lip. This reduces friction.

- Instroke: As the rod retracts, the GSJ Seal Step Seal is designed with a sharp “scraping” angle. It pumps that oil film back into the cylinder.

If the oil film is too thick, you get external leakage. If it is too thin, the seal burns. QZSEALS optimizes the lip geometry to control this film thickness perfectly.

Principle 4: Friction and the Stick-Slip Effect

Friction is the resistance to motion. In sealing, we deal with two types: static (breakout) and dynamic (running).

The Stick-Slip Phenomenon

Rubber has high static friction. When a cylinder has been sitting still, it takes extra force to get it moving. The seal “sticks,” then “slips” forward, then sticks again. This causes vibration and noise.

The Solution: PTFE.

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) has a static friction coefficient almost equal to its dynamic friction.

Products like the GSF Piston Seal Glyd Ring use a PTFE face. This eliminates stick-slip, allowing for the smooth, precise movement required in robotics and elevators.

Principle 5: Extrusion and the E-Gap

Under high pressure, a seal acts like a viscous fluid. It wants to flow into the gap between the piston and the cylinder wall (the extrusion gap or E-Gap).

Resisting Deformation

If the seal flows into this gap, pieces will be nibbled off, leading to failure.

- Material Modulus: We use harder materials like Polyurethane or filled PTFE to resist flow.

- Anti-Extrusion Rings: The SPGW Piston Seal incorporates hard polyacetal back-up rings. These rings bridge the E-Gap, creating a zero-clearance wall that prevents the softer sealing element from extruding.

Principle 6: Temperature and Thermal Expansion

Physics dictates that materials expand when heated and contract when cooled. However, steel and rubber expand at very different rates.

Managing Thermal Dynamics

In a hot environment, a seal might expand and create too much friction. In the cold, it shrinks and loses its “squeeze.”

- High Temp: We use PEEK or Metal O-Rings because their thermal properties are stable at high heat.

- Low Temp: We use special silicone or Stainless Steel 301 Helicoil Springs to maintain contact pressure when the polymer shrinks.

- Guidance: Phenolic Resin with Fabric Guide Tape is cut with a “scarf joint” (an angled gap). This gap closes up as the ring heats and expands, preventing the ring from binding in the cylinder.

Conclusion: Engineering Reliability

Sealing is not about guessing; it is about calculating. By understanding squeeze, pressure energization, lubrication films, and thermal dynamics, QZSEALS engineers solutions that predict and prevent failure of hydraulic seals.

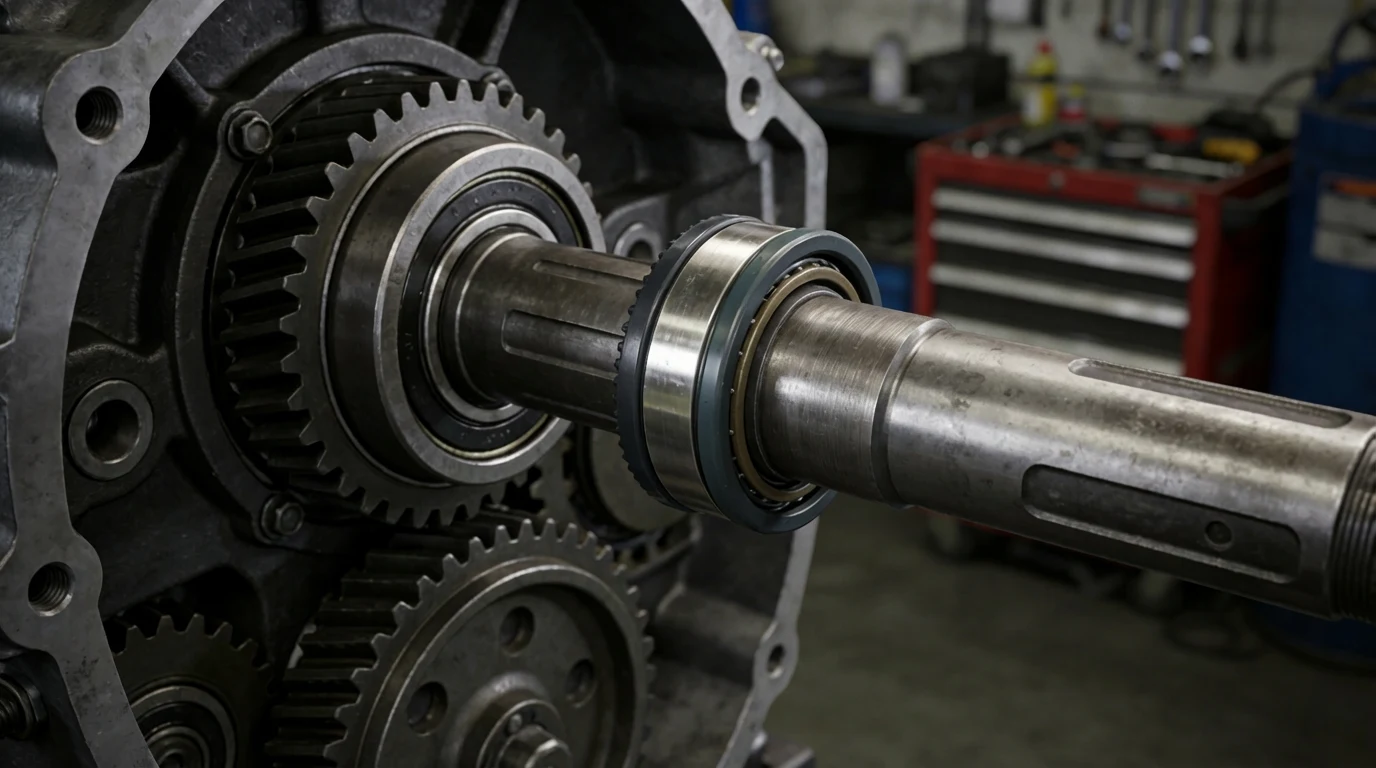

When you choose a QZSEALS product—whether a complex Gear Pump Seal or a simple PDR Wiper Seal—you are choosing a component designed with a deep understanding of physics.

Explore our technically engineered solutions in Rod Seals, Piston Seals, and Wiper Seals. Let us apply the science of sealing to your application.