Introduction: Beyond the Catalog – Seal Selection as a Critical Design Discipline

In the intricate process of machine design, seal selection is often relegated to a final, seemingly minor detail—a part number chosen from a catalog based on size and basic fluid compatibility. This approach, however, fundamentally misunderstands the role of a seal. A seal is not merely a passive component; it is an active, dynamic element and a critical point of engineering design control within a larger system.

The decision-making process behind its selection is a rigorous engineering design discipline in its own right, one that demands a holistic understanding of mechanical reliability, material science, and tribology. The consequences of suboptimal choices in sealing solutions are severe, extending far beyond a simple leak to include premature equipment failure, costly unscheduled downtime, compromised safety, and environmental non-compliance. Conversely, a correctly specified seal enhances seal performance and is a cornerstone of mechanical reliability and longevity.

This guide is designed to elevate the conversation from simple part selection to a systematic process of engineering design. It provides a blueprint for engineers, designers, and technicians to navigate the complex landscape of sealing solutions. We will move beyond the “what” and “where” of seals—covered extensively in foundational guides—to focus on the “why” and “how” of seal selection. This involves a multi-phased approach that begins with a deep analysis of the application’s demands, progresses through a methodical evaluation of material science and design trade-offs, and culminates in the hardware integration of the seal. By treating seal selection with the engineering diligence it deserves, we can move from a position of reactive problem-solving to one of proactive design, building mechanical reliability into the very DNA of our systems.

Phase 1: The Discovery and Definition Stage – The STAMPE Framework

The foundation of any successful engineering design project is a comprehensive and accurate definition of the problem. Before a single material or profile can be considered, every aspect of the seal’s operating environment must be meticulously documented and understood. The industry-standard STAMPS acronym is an excellent starting point, which we will expand to STAMPE to include the crucial factor of the external Environment and Expectations.

S – Size

This goes beyond simple nominal dimensions. It involves a detailed understanding of the physical space and tolerances.

- Hardware Dimensions: What are the precise nominal and tolerance ranges for the rod diameter, bore diameter, and groove dimensions? Understanding the full tolerance stack-up is essential for calculating the minimum and maximum extrusion gaps and compression squeeze.

- Space Constraints: Are there any axial or radial space limitations that might preclude the use of a more robust, multi-part seal and necessitate a more compact solution?

- Standard vs. Custom: Do the dimensions conform to an industry standard (e.g., AS568 for O-Rings), or will a custom-machined seal be required?

T – Temperature

Temperature directly governs material science choices and ultimately affects seal performance.

- Operating Range: What are the minimum and maximum continuous operating temperatures?

- Thermal Cycling: Does the application experience significant temperature swings? This can cause differential thermal expansion between the seal and hardware, a primary challenge for static seals that can be addressed by resilient solutions like Hollow Metal O-Rings.

- Excursions and Spikes: Are there short-term temperature spikes or heat sources (like friction in high-speed rotary applications) that must be accounted for?

A – Application

This defines the mechanical function and context of the seal.

- Type of Motion: Is it static, reciprocating, rotary, or oscillating? Each motion requires a completely different seal design philosophy.

- Function within the System: Is it a primary pressure-retaining seal like a Piston Seal, an external containment seal like a Rod Seal, or a protective seal like a Wiper Seal?

- Hardware Details: What are the mating surface materials? Is the hardware prone to side-loading or eccentricity? This information is vital for specifying guiding elements like Wear Rings in seal performance optimization.

M – Media

Covers every substance the seal contacts, influencing material science and tribology.

- Primary Fluid/Gas: What is the primary medium being sealed? Its chemical composition, viscosity, and state (liquid or gas) are paramount.

- Secondary Exposure: Will the seal be exposed to cleaning fluids (CIP/SIP), atmospheric humidity, ozone, radiation, or other environmental chemicals? A seal compatible with the process fluid can still be destroyed by an aggressive cleaning cycle. This is where the near-universal compatibility of PTFE Gaskets and seals becomes invaluable.

- Abrasives: Does the media contain abrasive particles or slurries? This will heavily influence the selection of wear-resistant materials.

P – Pressure

Defines the forces acting on the seal, critical for seal performance.

- Operating Pressure: What is the normal working pressure range?

- Pressure Spikes and Vacuum: Is the system subject to pressure spikes, shock loads, or vacuum conditions? High pressure necessitates materials with high extrusion resistance, while vacuum requires seals that do not rely on pressure energization.

- Direction: Is the pressure unidirectional, bidirectional (as in a double-acting cylinder), or external?

E – Environment and Expectations

This new category captures critical external factors and performance requirements.

- External Environment: Is the equipment operating in a dirty, dusty environment (e.g., construction), a sanitary environment (e.g., food processing), or an explosive atmosphere (ATEX)?

- Life Expectancy: What is the required service life or mean time between failures (MTBF)? A seal for a disposable medical device has vastly different requirements than one for a subsea oil wellhead.

- Leakage Rate: What is the acceptable leakage rate for sealing solutions? Is it zero visible leakage, or a specific, quantifiable rate (e.g., in gas sealing)?

- Regulatory Compliance: Does the seal need to comply with industry standards such as FDA, NSF, or NORSOK?

Only after every one of these questions has a clear, documented answer can the process of selecting a specific solution begin.

Phase 2: Material Selection – A Pyramid of Performance and Trade-Offs

With the application fully defined, the next phase is to identify a suitable Sealing Material. This is not a search for a “perfect” material, but a process of navigating a complex series of trade-offs between performance, cost, and processability. It is helpful to think of materials in a pyramid of performance.

Level 1 (Base): Standard Elastomers

This level includes the workhorse materials for general industrial applications.

- Nitrile (NBR): The default choice for petroleum-based oils and fuels in moderate temperatures. Excellent physical properties and low cost.

- EPDM: The preferred choice for water, steam, and brake fluids. Poor resistance to petroleum oils.

- Neoprene (CR): A good generalist with moderate resistance to oils and weather.

Trade-Offs: Low cost and wide availability, but limited by temperature (typically ~100-125°C) and specific chemical compatibility.

Level 2 (Mid-Tier): High-Performance Elastomers

When the base level is insufficient, this tier offers enhanced temperature and chemical resistance.

- Fluorocarbon (FKM/Viton™): The go-to for higher temperatures (up to 200°C) and broad chemical resistance, especially to fuels and mineral acids.

- Silicone (VMQ): Offers the widest temperature range of any elastomer (from -60°C to 200°C+) but has poor mechanical strength, making it better for static applications.

- Hydrogenated Nitrile (HNBR): An upgraded version of NBR with better thermal and mechanical properties.

Trade-Offs: Significantly better performance than standard elastomers, but at a higher cost. Still possesses the inherent limitations of rubber-based polymers.

Level 3 (High-Performance): Fluoropolymers and Engineering Thermoplastics

This level moves beyond traditional elastomers for extreme chemical and thermal challenges.

- Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE): Offers near-universal chemical resistance and a vast temperature range. Its limitations (creep, poor memory) are overcome in advanced designs like Spring Energized Seals.

- Polyether Ether Ketone (PEEK): An exceptionally strong, rigid thermoplastic that retains its properties at very high temperatures. Used for structural components like PEEK Valve Plates and anti-extrusion rings.

- Polyurethane (PU): Not a high-temperature material, but its unmatched abrasion and tear resistance make it a top-tier choice for high-wear dynamic seals in hydraulic systems.

Trade-Offs: Ultimate chemical/thermal performance but requires more complex seal designs (e.g., spring energizing) to function effectively as a seal. Higher material and processing costs.

Level 4 (Apex): Metals and Composites

For the most extreme conditions where no polymer can survive.

- Stainless Steels, Nickel Alloys (Inconel®): Used for metal seals, springs, and casings in ultra-high temperature and corrosive environments. Required for components like Helical Springs in chemical-duty SES.

Trade-Offs: Ultimate performance window but requires extremely precise hardware and very high clamping loads. Highest cost.

Phase 3: Profile and Design Selection – Matching Geometry to Function

Once a material family has been identified, the engineer must select the physical geometry, or profile, of the seal. The choice is dictated primarily by the type of motion and the system pressure.

- For Static Applications: The choice is between the simplicity and effectiveness of an O-ring (in a correctly designed groove), the conformability and media resistance of a gasket, or the high-integrity performance of a metal seal for extreme conditions.

- For Reciprocating Applications: This requires a dedicated dynamic lip seal. A simple O-ring will often fail due to spiral twisting. The choice moves to U-cups, loaded U-cups (with an O-ring energizer), or multi-part piston/rod seals that often include integrated guide and anti-extrusion elements, such as the robust SPGW Piston Seal.

- For Rotary Applications: This demands a specialized radial lip seal (oil seal). The design must manage the hydrodynamic film to ensure lubrication without leakage. A standard TC Oil Seal is suitable for many applications, while a PTFE Oil Seal is required for higher speeds or aggressive media.

- For Extreme “Problem” Applications: When an application features a combination of extreme challenges (e.g., cryogenic temperatures AND dynamic motion), the spring energized seal often becomes the default solution, as its composite design can be tailored to meet multiple demanding criteria simultaneously.

For a detailed overview of industrial seals, SKF provides an extensive catalog of sealing solutions SKF Seals.

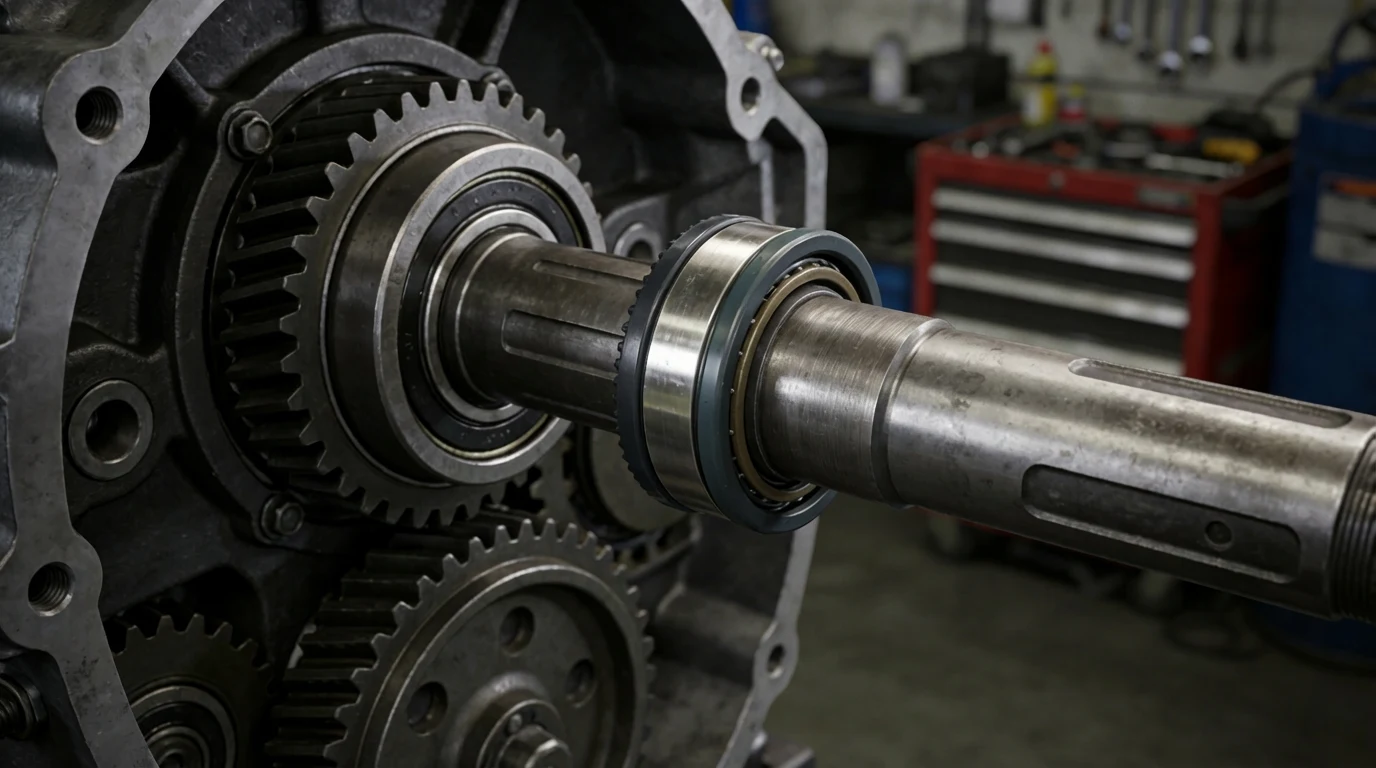

It is also at this stage that the concept of a “sealing system” must be applied. For instance, in a hydraulic rod application, one does not simply choose a rod seal. One designs a system consisting of a primary rod seal, a secondary buffer seal to absorb pressure spikes, and an external wiper seal to exclude contamination.

Phase 4: Hardware Integration and Validation – Designing the System for Success

The seal is only as good as the hardware in which it is installed. This phase ensures that the mechanical environment is optimized for the chosen seal’s performance and longevity.

- Surface Finish: The roughness, lay, and texture of the mating hardware surfaces must conform to the seal manufacturer’s specifications. This is particularly critical for dynamic seals to prevent abrasion and ensure proper lubricant film formation.

- Gland/Groove Design: The geometry of the groove must provide the correct squeeze, prevent overfill, and provide adequate support for the seal under pressure.

- Extrusion Gap Control: The clearance between moving components must be minimized to prevent the seal from being extruded under pressure. This is a function of both machining tolerances and the use of guide elements like wear rings.

- Material Hardness and Compatibility: The hardware should be sufficiently hard to resist wear and must be galvanically compatible with any metallic elements of the seal to prevent corrosion.

- Validation and Testing: The final step is validation. This can range from simple material compatibility soak tests to full-scale prototype testing under simulated operating conditions. This phase verifies that the selections made in the previous phases will perform as expected in the real world. Iteration is a key part of this process; initial testing may reveal the need to adjust the material, profile, or hardware design.

Conclusion: From Component Selection to Engineered Reliability

The journey from a set of abstract operational requirements to a reliable, long-lasting sealed joint is a testament to the power of a systematic engineering process. It demonstrates that seal selection is not a task to be taken lightly, but a multi-faceted design discipline that forms a critical pillar of machine reliability. By following a structured blueprint—beginning with a rigorous definition of the challenge (STAMPE), progressing through a logical hierarchy of material trade-offs, matching the seal’s geometry to its function, and finally, meticulously engineering the hardware environment—we transform the act of selection from a guess into a science.

This process ensures that all variables are considered, and all potential failure modes are proactively addressed during the design phase, where changes are least expensive. It builds a foundation of robustness that pays dividends throughout the entire lifecycle of the equipment. For any organization committed to achieving the highest standards of performance and reliability, embracing this comprehensive approach to seal selection is not just best practice; it is a fundamental necessity.